Dr. Renatta Craven made the most of the Carolina Covenant

The journey of one of the first students to use the financial aid package shows the power of the program.

Sometimes when she looks at her three daughters, Dr. Renatta Craven thinks about her own childhood and all she had to overcome.

She never met her father. Her mother died when she was 3. Ida, her loving grandmother in Raleigh, adopted and raised her, but times were tough. When summer nights were particularly brutal, she slept in the only room with air conditioning — the kitchen.

“You don’t realize how problematic things are until you grow up a bit,” said Craven ’08 ’15 (MD).

Now a pediatrician in the Seattle area, Craven often sees patients with “adverse childhood experiences.” Craven didn’t know the term as a child but realized as an adult that she “had a bag of them” herself.

Her work is therapeutic for Craven, who came to UNC-Chapel Hill in 2004 as one of the University’s first Carolina Covenant Scholars.

Twenty years later, 11,000-plus students have benefitted from the Covenant, a financial aid package and network of support that allows students to graduate from Carolina debt-free.

“When I graduated residency and got my first real job, I felt like I was breathing fresh air and could pull my whole body out of that pit and dust myself off,” she said. “I could look around me and be like, ‘OK, I can breathe. I can take a breath.’ That was liberating, and that’s what the Carolina Covenant has the potential to provide.”

“At the time I didn’t realize this, but I think my whole life was preparing me to be a pediatrician,” Craven said. (Submitted photo)

‘Complete elation’

Growing up, Craven excelled as a student but didn’t receive much academic support.

“My grandmother took care of me the best way she could have,” Craven said. “But this was an older woman without a high school education. She didn’t know how to advocate for me in the public school setting.”

Craven learned to advocate for herself. She spoke up when an administrative error kept her from enrolling in academically gifted classes in middle school. In high school, she had to twice convince a dismissive school counselor that she qualified for financial assistance to pay for SAT and college prep courses.

But when Craven, already accepted into Carolina at the time, received a letter in the mail about her inclusion in the Carolina Covenant, she finally felt that someone was advocating for her.

“It took a really long time to digest that news,” she said. “I remember feeling complete elation.”

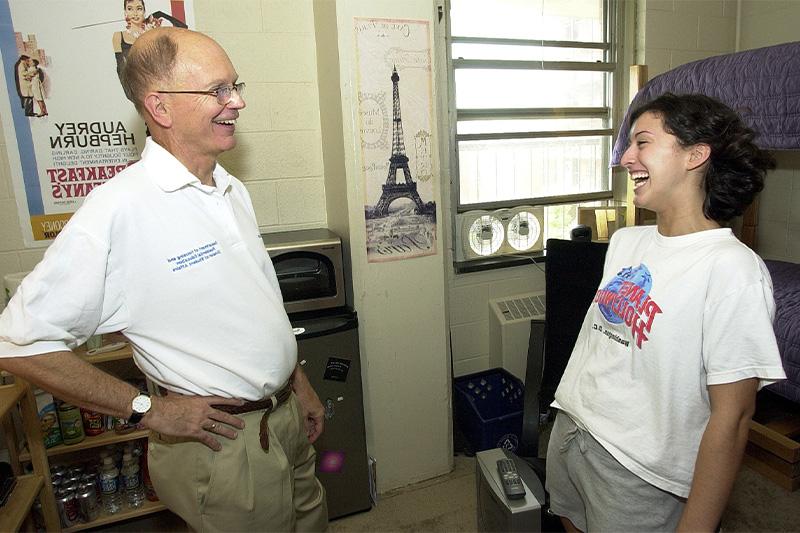

Craven speaking with then Carolina Chancellor James Moeser in 2004 in her Morrison Residence Hall dorm room. (Dan Sears/UNC-Chapel Hill)

Making the most of the Covenant

Once at her dream school, Craven began studying biology so she could become a doctor. But when she couldn’t shake worries that she wouldn’t get accepted into medical school, she came up with a different plan to support herself and her grandmother, deciding to become a nurse instead.

Later — when her doubts about medical school dissipated — Craven enrolled in the UNC School of Medicine. She called this a “jaw-dropping experience” and one she was proud to share with her grandmother.

“This woman who didn’t graduate high school herself and grew up on a tobacco farm in Johnston County, North Carolina … she just could not believe this daughter she raised was going to be a doctor.”

Ida died during Craven’s third year of medical school, an event that changed the trajectory of Craven’s path and led her to Seattle for a residency at one of the nation’s top children’s hospitals.

The pediatrician has a family of her own and a medical career her grandmother never imagined she could achieve, a career made possible by the Carolina Covenant.

“They made an investment in me,” Craven said, “and I hope I am honoring that investment.”